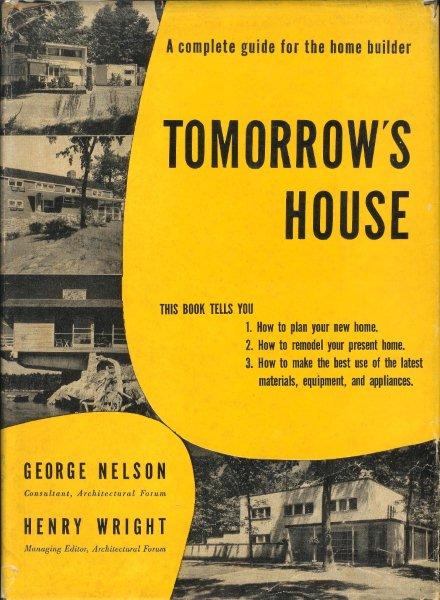

In his 1946 book “Tomorrow’s House’, George Nelson (along with Henry Wright) created a popular, post-war consumer pattern book defining the "house of the future". Equal parts designer, critic, writer, gadfly, and teacher, Nelson at the time was setting up his own industrial design shop, had just been named Herman Miller’s new Director of Design, and was in the process of helping introduce what has become defined as the ‘post war modernism’ (I’ll leave this distinction to the small army of historians who can talk more eloquently about design in this era).

Concluding ‘Tomorrow’s House’, Nelson sets out educating the reader on selecting an architect, negotiating with a contractor, obtaining financing, etc. The passage below, in Nelson’s erudite prose, caught my attention recently as it illuminates so many of the issues we still face in setting ‘appropriate’ fees commensurate with our efforts:

"It might be added here that there is no reason to be afraid of going to see a firm of architects simply because it has a first-class reputation. Architects as a rule have fee scales which do not vary tremendously, and many people find to their surprise that the fee charged by the best available firm is frequently no greater than that asked by its less talented competitors.

Among the better offices it is fairly standard practice to charge at least 10 percent of the cost of a house for architectural design services and supervision. A few offices go above this figure, and some will go below. There are architects-many of them-who will set their fees at 6 percent or even lower. These, however, do not fit into the group whose work appears here.

Perhaps you would like to know why architects have to charge a 10 percent fee to do a decent job on a modern house. A little arithmetic should make this fairly clear. Let us assume that a house is going to cost around $12,000. This puts the architect's fee somewhere in the neighborhood of $1,200. Of this amount he will be able to recapture $300 to $400, if he is lucky, as payment for his time, which may run from three to six months or more. The remainder-say $850-has got to pay his overhead, salaries to draftsmen, and the other expenses of his business. In return for this he will camp on your doorstep, practically psychoanalyze the family, try to distinguish what you want from what you say you want, produce a series of drawings from which the house can be satisfactorily constructed and equipped, negotiate with bidders to get the house within the budget, and arrange for changes in the plans and details. And, into the bargain, he will probably give advice on furniture, color schemes, fabrics, and landscaping, in the event that specialists in these fields are not engaged: That is why a conscientious architect cannot undertake to do a reasonably good job on a custom built house for less than 10 percent. Probably, if he were as good a businessman as he is a technician and artist, he would charge considerably more.

There is another situation that has to be met. Rather early in the game your architect will find that existing home equipment, whether for lighting, storage, or some other purpose, is not properly designed, and he will suggest, frequently with good reason, that a certain amount of special work be done. This involves dealing with a miscellaneous assortment of electrical supply people, metal workers, hardware firms, and others, in an• effort to concoct something superior to the stock article.

Some people find that this part of the process of designing a modern house is great fun. But even so, it is a lot of work, too.” (Nelson & Wright, “Tommorrow’s House”, 1946, Simon & Schuster, p.200).

60+ years on this passage is illuminating, perhaps more so as it’s geared towards a consumer of our services. Why? Because it shows just how little we’ve moved off a few key areas:

A proliferation of specialists –note that Nelson points out that, essentially, an interior designer and landscape architect would/should be a part of the equation, in addition to the architect. More important is the implication that the homeowner would contract with them directly, instead of the architect putting that under our scope of work in many cases. Or it leaves unresolved the question of how these are to be integrated, the time the architect would require to integrate their work and how the architect would be paid, etc. Now? We’ve multiplied the number of consultants (lighting, AV, security, commissioning, code, etc.) as the number of possible systems have proliferated. Very few firms would (or even could if the desire was there) attempt to host all these under a single banner. Integrate perhaps, but not host.

An over extended commitment of time – how many architects will really ‘camp out on your doorstep’? Hyperbole to be sure, but there’s a subtly delivered message about the raw time spent in the service of a project. Why? Is that simply a general professional complaint that’s echoed through the ages? Again, perhaps so. At the very least, as a whole, have we become better at correlating time/effort with our clients assumptions?

A ‘starving artist’ mentality – yep. Still here. Still detrimental. Still… yeah.

“Someone else” undercutting (and probably under delivering) fees – enough ink has been spilled on this topic….except for one new wrinkle that hadn’t occurred to me before and which we’ll wrap up with below: the idea of a “lower fee” was pushing up against much stronger, more defined ‘norms’ related to an architect’s compensation. Nelson, actually, does an admirable job of acknowledging the issue (“there are architects…who will set their fees at 6% or lower…”), clarifying that ‘those’ architects work isn’t shown here (a jab at their implied quality), and then proceeding to demonstrate why a ‘normal’ fee is barely adequate for the effort the architect is expending. His value argument is wholly self-contained: It’s effort “X” that’s the great value.

(As a sidebar: really, if the public thinks we are well compensated, why are we so insistent on undermining that perception? Peter Eisenman, of all people, made a great observation once that clients don’t take you seriously until it costs them real money. And the longer I practice, the more this axiom proves to be doubly true in a “fee for service” arrangement).

Finally, one of the lynchpins in this passage: Fee schedules – I’m finally convinced we’ve never really escaped from their overarching influence, even this far removed from their being in force. As mentioned above, this passage from 1946 shows a reliance on the fee schedule to establish a ‘norm’ for compensation, something that’s tied to an assumed level of ‘basic services’. Over time, as the complexity of buildings changed and the architect’s scope evolved, the schedules/normative fees were adjusted accordingly. In a bitter twist of fate, the extinguishing of the schedules in 1972 roughly corresponded to the nascent explosion of building systems and technologies. Our scope of work, especially with regards to building systems design/coordination, began to multiply but our fees did not. Why? Why have our fee rates (not literal amounts) remained unchanged in 40 years? It would take some additional research, but my hypothesis is that we’ve allowed the extinction of the schedules to essentially ‘cap’ what the broadly accepted fees are. In short, we’re still stuck on that schedule, even though we’ve continued to allow greater scopes of work to be defined (both literally but more important, culturally) as ‘basic services’. That’s really the key: what truly constitutes ‘basic” (or minimum or essential) services an architect “must” provide as part of their legal and ethical obligations?

Contracts (especially the AIA’s Owner-Architect Agreement) define a core set of minimum services as ‘basic’. Once upon a time, these were very explicitly tied to the fee schedules. So, if the project’s scope went up in complexity, the basic service could remain the same but the fee expectation was ratcheted up. Already, in Nelson’s writing, we can see how the alignment of ‘actual’ services could be seen as disproportionate to compensation and why certain thresholds (the schedules) needed to be maintained. (I’m allowing for his writing to be somewhat ironic and to help press a case for a base fee expectation in the consumer’s mind. But isn’t that our point?). But I don't see this as the problem. We can define, all day long, what an 'appropriate' fee SHOULD be, in our eyes. The problem is: this doesn't match our client's expectations. Which, I'm contending, are still largely being driven by a 40+ year old schedule. What's changed is the assumption of scope embodied in that fee and the increasing disconnect it has to our stated desires.

There’s enough to unpack in this area that it’s going to take a few posts to work through. Formal fee schedules are gone. So, how do we define a truly ‘basic’ level of service, one that helps properly correlate our efforts with a basic level of compensation in the minds of our clients? Is this even possible? (The Union of International Architects has taken a shot - you can see their fee compensation calculations here). Can we reach an agreement on what these services constitute? Could, as one example, the AIA ‘demand’ a level of services as a condition of membership (ie, a member can’t offer a lower level of service than the ‘basic’)? What’s clear, looking back, is that we’ve got to move forward on clarifying the basics of what we do with the public and do a better job correlating that with some kind of baseline that’s easily understood.

Central to the blog is a long running interest in how we construct practices that enable and promote the kind of work we are all most interested in. From how firms are run, structured, and constructed, the main focus will be on exploring, expanding and demystifying how firms operate. I’ll be interviewing different practices – from startups to nationally recognized firms, bringing to print at least one a month. Our focus will be connecting Archinect readers with the business of practice.

24 Comments

Gregory great quality post glad you are out of hibernation. Starting with well defined basic services as foundation for fees and defining our social roles is definitely step one. With that said I see a few immediate complications. The first of which is if we started with the state and local laws defining when an architect is required. Most places the home owner can pull permits for home construction. Often a Professional Engineer can sign and seal the same scope. The second issue is the builder often lumps into their cost estimate the sign and seal and depending on state the method for presenting project delivery this way can be interpreted as illegal. If AIA members agreed on what their basic services were and maybe excluded assisting builders this way then maybe DBIA architect members would provide this assistance. Organizations could stand for basic services but it would probably still confuse the public to find architects operating differently depending on title after their name. For instance I am an RA - unaffiliated professional. Thirdly the tools play a huge factor in all this even though most would disagree especially older generations. Lets take BIM vs 2D drafting. If I do the house in BIM (revit) at no real additional time (a few clicks) I can offer the client 3D renderings - any view. So to compete with another firm I could presumably throw in the 3D for free and match other firms fee with more services. There are plenty more examples but this shows how basic service can quickly be complicated by the tool alone. The fourth is fabrication, not traditionally a service, which is mainly due to tools. Architects can now offer shop drawing level services and fabrication which crosses over into the contractors realm thanks to computers. If you are making that cross over the next step to including management of sub contractors seems natural and now as the architect your basic services become very murky. Construction Management as construction administration phase services. On one hand the law appears to make it clear but project delivery can rearrange that easily and the tools can extend or limit the possibilities of the architect can provide. It may be better to have the AEC O industry to define what the Architect Engineer Contractor and Owners roles can be? Or define define our possible basic services within the complete industry. For instance "on thus job we are going full AEC service, but for this owner we are acting as AE consultants only"...etc

I don't disagree, but those who are most familiar with these tools are often recent graduates who would do anything to get a gig.

On the other hand, charging for "air" can only last so long until someone figures it out. As many owners often staff in-house technicians and professionals, charging for a service that comes with the tool automatically can only be profitable for so long.

The separation described in Gregory's quote with architect from draftsmen isn't so clear anymore to the general public. This would be the argument to insist licensure clearly separates the two, but convince the public of this, especially when many "designers" do architecture.

Chris -

I'll have more time to respond tonight - for me, the split in labor is less important than clarifying what is 'basic' and 'additional'. Meaning, if we say 'I provide contract documents' (which, by the way, is the more correct legal term, not construction documents), what does that entail? I have an agency we work with that lists all of this as "basic services", even though their own contract recognizes several of them as 'additional' services:

So, how many other contracts include all that as 'basic services'? Certainly not the AIA.

But all of those are tied to a fee schedule that was, literally, developed 30 years ago (in our case) and which hasn't been updated since. The contracts have - and are undergoing revisions now - but owner's are really reluctant to move that needle...

I learned to write proposals from someone who wrote their own differently for each job and negotiated services instead of reducing fees, so your list would be line items with numbers. The danger is if you exclude one item it often has a domino effect on others...of course what are all the services? Which is what I believe you are getting at. I often learn the hard way on job types I have never done before - what my basic services should of been, and to your point I think this is a major issue effecting low compensation. I am also learning listing what you wont do can be problematic. Sometimes I try to provide the client with a list of possible scopes of services to determine what they expect of me...this often gets thrown out by clients who feel they may lose control or get taken for minor disagreements...so I get paid to then make "documents" as required...

Chris - for now, I'm simply saying that the term 'basic services' used to have a direct link to an almost universally accepted definition, which was also then correlated to a fee schedule. Because those 2 items were developed in tandem, there was a more causal relationship to a bottom threshold and also to firms that would try to move off that baseline (up or down). A truly in-demand firm could restrict their "supply" (by staying a certain size, limiting the # of jobs they took on, etc.) and raise their prices above that benchmark to the degree the market would support it. Likewise, someone could offer to do it for less. But at least most clients and architects were starting off with the same understanding of what the baseline was.

That's been tossed out for the last 40 years, not to our benefit. Owners keep trying to work more into what the definition of 'basic' is and we're not keeping up.

None of this is really talking about how this could be fixed or how we might think about proposals now. Working through that in the next couple of posts.

looking forward to them

Man this is really interesting stuff and I’ve enjoyed everyones work here, great writing. I am a 40 year career guy and have lived my whole life with this stuff. I think you state the issue succinctly and the history and I’m looking forward to your exploration into the solutions. I think I have a lot to contribute here and look forward to the opportunity.

In the mean time though, something to think about, the idea of base lists of services and base fees with clients doesn’t work. It draws out words like “additional”, “non-standard”, “non-traditional” “extra” etc. that makes clients knees raise-up. Its like stirring dominos around on a table before the game starts. It’s up to architects to define the services needed and to craft a service/fee arrangement that is both serviceable and competitive. Being good at this, the business side of architecture, is what keeps you in business and thriving. I’ve offered this elsewhere - having these lists is essential to our profession internally to assure profitability and balance. Finding effective ways to do this legally is the solution to all this.

Finally, I think Nelson’s analogy of value, putting the dollar amount in perspective is extremely astute. Placing the value/ratio of every stated fee amount should be followed with a footnote of this kind.

Carrera good point on the internal vs external lists. If anything the internal list is good for that occasional savvy developer or builder......Greg I am sure you are busy and looking forward to your next post.

Think I will go and buy some house plans off the internet.....they do it for $1.25 a square foot. Why do I need an Architect? They have built this house before so there shouldn't be any problems.

snooker - why aren't you the architect who's selling that same plan 20 times at $1.25/sf? seems to me like you'd be at $25/sf, which is really, really good for one house design. especially since you'd have done the design only one time. on a 2,500sf house, that works out to $62,500. if you can crank one out every six months... yeah, i think you'd be just fine.

Architect's fee in 1946: $1,200.

Median US annual income in 1946: $2,600.

Architect Fee in 2014: $43,750.

Median U.S. Annual Income in 2014: $51,371

Where are we losing ground?. Our fee schedule is still valid after all these years, the cost of constructon has bolstered our take.

Miles, been looking, where did the 1200 come from? The one I stated is based on 2,500 SF X $175./SF = $475,500 X 10%.

^ The article at the top.

miles - sorry, i'm a little confused as to what you're trying to correlate. the fee for a single house, yes, may be very high relative to the median income but the average house price (from here, where i think you're pulling your numbers from) is 5,500. so, this house is already likely to be 2x the average; one would assume the clients reading that book (and able to pay 10% for an architect's fee) were making more than the median.

if you're correlating that designing 2.2 houses would get you to the median income of the u.s.(in 1946), it seems like that would certainly hold true for today (even using carrera's numbers, it looks better). nelson's point, though, is that the fee wasn't a straight-to-the-pocket fee - it had to cover overhead, draftsmen, etc. so, presumably, one would need to design more than a few homes to exceed the median. or is that the point you're making - that even doing several homes would *just* get you to the median?

(edited to include the link)

Architecture was and still is a service for the top 5%.

I of course totally concur with Miles but there are some like Mockbee’s Rural Studio at Auburn and Architecture for Humanity…and others....that keep us from being a total embarrassment.

http://www.ruralstudio.org/

http://architectureforhumanity.org/

The fact that architecture is a "Service" is the reason we can't affect the residential market for 99% of people. Who can qualify for a construction loan? Who can afford the time this process takes? Architecture is not elitist because good design itself must be expensive, its elitist because the business model is designed in a way that is not accessible to the masses. We should IMO be looking at home design more like a product. We should approach this market more like industrial designers approach product design. The custom hotrod business will never dominate the auto market.

jla - i totally agree and if you've read some of my previous posts, they articulate a similar position (that not everything we do should be a service - there is a place for 'product' in our mix). we, as a firm, do sell our designs through a homeplan site. i don't know too many people, though, paying the bills just with the document sales. still, for the right firm, it can work. another alternative that's way more 'product' like is compiling your best practices into a book. sarah susanka has made a whole career out of hitting one book at the right time for the right audience. nothing really original in it - just a great compendium at the right time.

I like this discussion and most particularly the issue of fees, but the issue of architects designing houses is a bit of a dead end. Like Miles has demonstrated it’s a 5% thing for architects, the prospect of architects designing for the masses is lost to the wind. The reason is that when an average persons wants to move they need to sell their existing first then once sold they have what 30-60 days to get out and find another. This kind of housing (if new) has to be ready-to-go and of course this is the spec-home market….so if an architect wants to contribute to this market they have to get speculative and design-build….but there are caveats besides money.

After my retirement from the game, building houses was on my bucket-list so I designed and built two spec homes as investments and to play out my ideas….it didn’t turn out pretty. I didn’t do anything modernist or radical just well styled traditional designs that were of genuine natural materials with good solid construction that I thought was a lost art and made them very energy efficient. The first thing that happened is I made up some really tasteful signs with my name and AIA…used the AIA logo for distinction. The signs kept disappearing, not the frame but the panel and it happened over and over costing me $100 a pop. I looked everywhere in the farm fields, everywhere and could never find them. Finally I got suspicious and installed a camera and I found some young fuck builder in his $45k pick-up truck stealing my signs out of intimidation. Then the second problem – I got the idea that the stairs to the upstairs bedrooms should be in the rear of the house for privacy instead of in the foyer....nearly everybody that came through on open-house Sunday said “where are the stairs?” “That’s strange”. That house sat on the market for well over a year during the Boom and was stepped over by the vinyl versions down the street. I eventually sold the house at a big loss just to get rid of it.

I designed a number of custom homes too during my career and have watched mine and others just linger on the resale market when put up for sale and when purchased dumpsters appear and the wallpaper flies. I love the building type and love even more watching imaginative architects reach for solutions. One of my favorite books is Pre Fab by Arieff & Burkhart just full of prefab houses by architects from all over the world - but that sadly go nowhere. I wonder if we are really doing anyone any favors by being in this market at all.

I just have to add that I worked with Don Scholz (Scholz Homes) as a kid in the late 60’s. While he wasn’t an architect or engineer he was a visionary in housing. First on many fronts with panelization and prefabrication. Back then we designed a house called The 960 which was a 960 square foot home meant for mass market. He built a factory to build them and during my time there he commissioned an aerial rendering of a futuristic subdivision with multiple cargo helicopters flying in the houses. Been searching through the attic to find it, no luck yet. His son John whom I have kept in touch with, did become an architect and carry on the family tradition but holds the opposite distinction of designing the most expensive house in the world - if you could call that an accomplishment…and so it goes, or should I say - so there it went.

http://www.ncmodernist.org/scholz.htm

http://www.scholz.us/info.php

Yeah, it's tough. The comp. appraisal system does not figure in the qualitative things that make architecture "good." The comp process is more like a check list of stuff and size. It's as dumb as valuing cars by the number of seats and cup holders. The RE appraisal system is a big hurdle but seems to weaken its clench a bit in certain areas.

jla-x, I knew of this problem of course but when I got up against the start of this last recession I still had the second house and had to refinance. When I did I knew it was going to be a comp problem but I met with the appraiser anyway and just sold the hell out of the design features and the quality of material I added, explaining that these things added value that he needed to consider and throughout the whole charade he just kept glancing at me with this “you’ve got to be shitting me” look. Yes you’re right this is another nail in the coffin, a big nail.

This problem seems to be isolated to houses but most all of my commercial projects got reappraised/refinanced at completion with the owners adding net worth to their vaults. I am soon to post a new thread to discuss appraisals from paper drawings to fruition and who really should benefit from the boost. Hope to see you there.

the university where my gf teaches has no architecture or interior design department. however, they do have some great old architecture books and i have many on a semi permanent check out. i found nelson's book there and it was last checked out on September 22, 1972.

I don't think it's true that architecture serves only the top 5%, it just serves everybody very badly. There's a lot of builder work that architects are completely unprepared to do thanks to an education and media ecosystem that belittles the day to day work. Every once and a while there'll be a look at shipping containers or vernacular construction the third world, even some cool ad-hoc buildings in cool settings, but not a lot on the everyday world of builders who spread plastic houses and retail strips across the land. Without the skill to design intelligently, economically, and beautifully, the developer will tell them to spread some decoration on a cheap box and we'll all laugh at the McMansion.

If you want to improve the service and therefore the fee architects receive, teach them to take people's desires and tastes seriously, be it modern, traditional, or purely practical. Teach them to build economically rather than drawing unbuildable designs for the exorbitant tuition charged. I have Nelson's book, and it's interesting on many levels.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.